Seven common web accessibility mistakes — and how to avoid them

The WCAG guidelines go into exhaustive detail about every aspect of web accessibility and how to adhere to the recommended standards. But over the past 10 years, I have seen seven very common mistakes that people make when producing web content, and fixing these issues will go a long way toward making your information more accessible to everyone.

1. Inaccessible documents

This is by far the most common issue I have seen when maintaining web content for government websites. The scenario is usually something along these lines:

- The organisation’s legal team sends through a PDF that absolutely has to go on the website right now.

- Because a Very Important Person signed the document, and because the legal team doesn’t know how to produce an accessible PDF containing a signature, they have scanned the printed document and emailed that to you.

- Since the document is just a scanned version, from a digital perspective it’s no better than a fax, or a screenshot of text. It contains no machine-readable text, and therefore the document fails to meet the most basic level of accessibility standards.

I have had to send these types of documents back to their owners, with a brief explanation for why they can’t be used online and how they can produce an accessible alternative, literally hundreds (and possibly even thousands) of times over the past 10 years. There are two easy ways around this.

- Use Adobe Acrobat Sign or a similar app to set up digital signatures for documents; or

- Omit signatures from documents and upload the unsigned version — so long as the physical copy of the signed version exists somewhere, you are legally covered.

Considering how easy Adobe and other software has made it to generate accessible PDFs, even with digital signatures, there’s really no good excuse for the “let’s scan this printout at the copier and email that to the Web Team” thing anymore. There is of course a broader discussion to be had around whether information should be shoved into PDFs and Word documents at all, because it’s far easier to make that information properly accessible if it’s actual text on a webpage rather than an attached document. However, at least in some circles (government especially) it’s often impractical to take the text-on-webpage approach. The bottom line here is that if you feel like you absolutely have to have your information buried in a PDF, the very least you can do is make that PDF actually readable.

2. “Click here”

The words “click here” are the bane of my existence. People who write links using “click here” or even just “here” are doing a serious disservice to website visitors, and they don’t even know it. A website link should give you some idea of what it will do and where it will take you before you click it. Consider the following two options:

- Click here

- View Rick Astley – “Never Gonna Give You Up” – YouTube video

Both of those links go to the same place. The difference is the first one doesn’t give you any context at all for what the link will do, while the second one tells you exactly what to expect (and therefore, you know not to click on it if you don’t want to).

It’s not enough to have the context for the link somewhere outside of the link, either. Plenty of people think this is just fine:

- To view Rick Astley’s music video for “Never Gonna Give You Up”, click here

To explain why this isn’t an acceptable way to write a link, I have to put you in the shoes of a blind user navigating your website. Screen reader software usually comes with a feature that identifies web page headings (more about those later) and links on the page. This acts as a shortcut for the user and allows them to skip between headings and links without having to wade through all the intervening text first.

What’s this person’s device going to say to them when they come across that link in the example sentence from earlier? “Click here.” That’s it. No context at all for them. Worse, if you’re like a lot of web content authors I’ve seen, you’ll have the words “click here” or “here” peppered throughout your text multiple times, so all this poor user is going to hear when they navigate through your page links is “click here” “here” “click here” “click here” — incredibly frustrating.

Telling people to “click here” also ignores the basic fact that a lot of your users — probably more than 2/3 of them — are going to be on a smartphone when they visit your site. They can’t “click” anything. They’ll understand what to do anyway — probably? — but you should avoid telling them to do something they fundamentally cannot do on the device they’re using.

The easiest way to get around this problem is to write the text in your links as though they were the only thing on the page. Imagine that all other text on the page went away, and all you were left with was the blue (or other colour) text with the underline beneath it, directing the user to do something or go somewhere. Your job is to make sure they understand exactly what that link does, without any other help outside of the link itself. Write your links as a short action phrase: “Go to (the name of the website)” or “Read (the name of the document)”.

3. Not using headings (or using them wrong)

Remember when I said blind users have screenreaders that can skip between headings? Do you know what happens for these users when you’ve used bold text for headings instead of actual h2, h3, or h4 heading text? You probably don’t know, but now you will: the screenreader doesn’t identify any headings, so it acts like there aren’t any. So the user can’t skip between headings, can’t identify the overall structure of the page at a glance, and has to wait for the screenreader to read out potentially almost the entire page before getting to the content they actually need.

Not using properly marked-up headings also means Google’s web crawler has a harder time identifying what your page is supposed to be about, which can cause your content to take a big hit on search engine optimisation, meaning people won’t find it as easily as they could have.

Another thing I see people doing is using headings stylistically and skipping the styles they don’t like. They’ll skip from h2 all the way down to h5, then go up to h3 for some reason, then back to h5… when you do this, what you’re telling both screenreaders and Google is to present the content in an order of hierarchy entirely different from what you might intend. If you don’t understand what I mean by that, the simpler version is that there’s a right and wrong way to use headings:

- h1 is the top-level heading for the page. This should be your page title. There shouldn’t be another h1 anywhere on the page. Most website CMS editors will let you use another h1 if you want to — but don’t.

- h2 is the actual top-level heading for the page content. This should be the first heading type you use when you want to carve up your page content into smaller chunks. If you think of your page as a book, and h1 as the title of that book, then h2 headings are the titles of your book’s chapters.

- h3 is a subheading under h2. This is a subsection within an h2 section.

- h4 is a subheading under h3. This is a sub-subsection within an h3 section.

- …and so on, from h5 down to h6.

The key here is not to skip around randomly from h2 to h4, or skip h2 altogether and go straight to h3. Headings do more than make text bigger and bolder — they tell software what the overall structure of the page actually is, like building a table of contents for a book. If you use headings non-hierarchically, you’ll confuse the software, and you’ll confuse your users — and Google. You don’t want that.

4. Jargon, jargon, and more jargon

If you’re writing for a specific kind of audience that already understands the language of whatever industry or field you’re presenting information for, then fine — go absolutely nuts with the jargon, highly technical language, and abbreviations. If you’re writing for a general audience, don’t do that. Use plain English wherever possible. Explain technical terms the first time they occur in your text. Spell out abbreviations the first time they show up, then use the abbreviation after that. Simplify your language as much as you can without losing the essential meaning of what you’re trying to say.

Some organisations try to fulfil this objective by producing “Easy Read” documents that use much simpler language and even diagrams to get the basic meaning across for people that might not be able to understand the content otherwise. This is a good approach, although it does mean creating and maintaining two entirely separate versions of the same content, which can get unwieldy very quickly. It’s perhaps better to take the opposite approach: make the text on your page as basic and widely-accessible as possible, and offer the more detailed, more technical version separately for the subset of your audience that needs this more detailed (and possibly more jargon-filled) information.

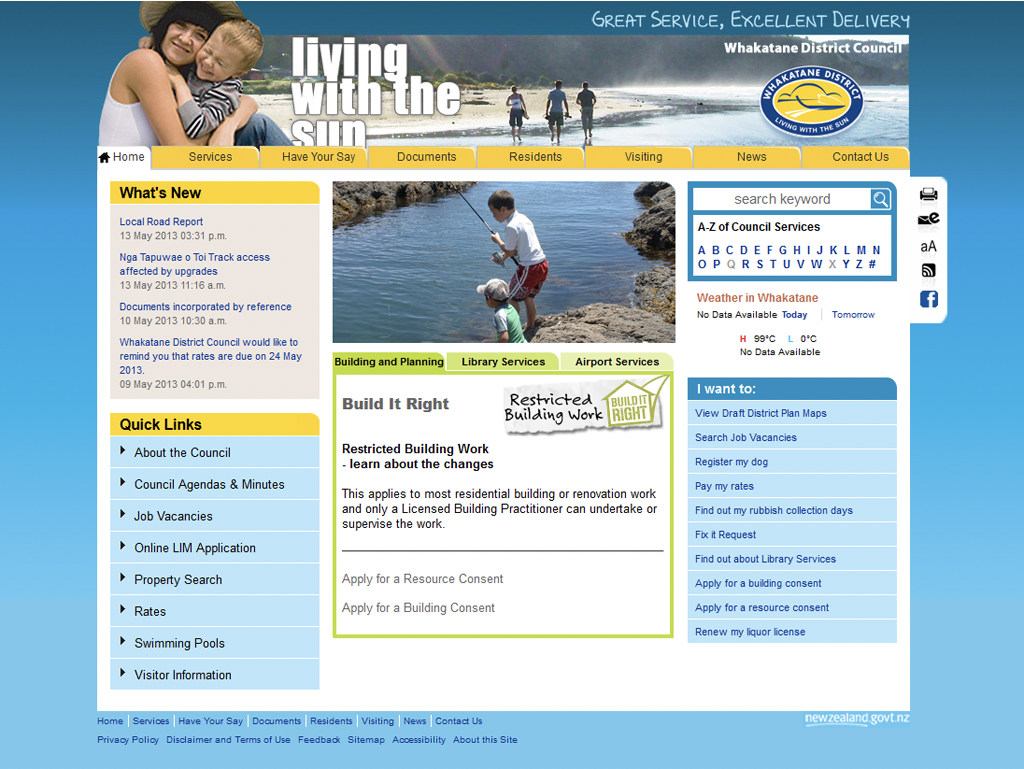

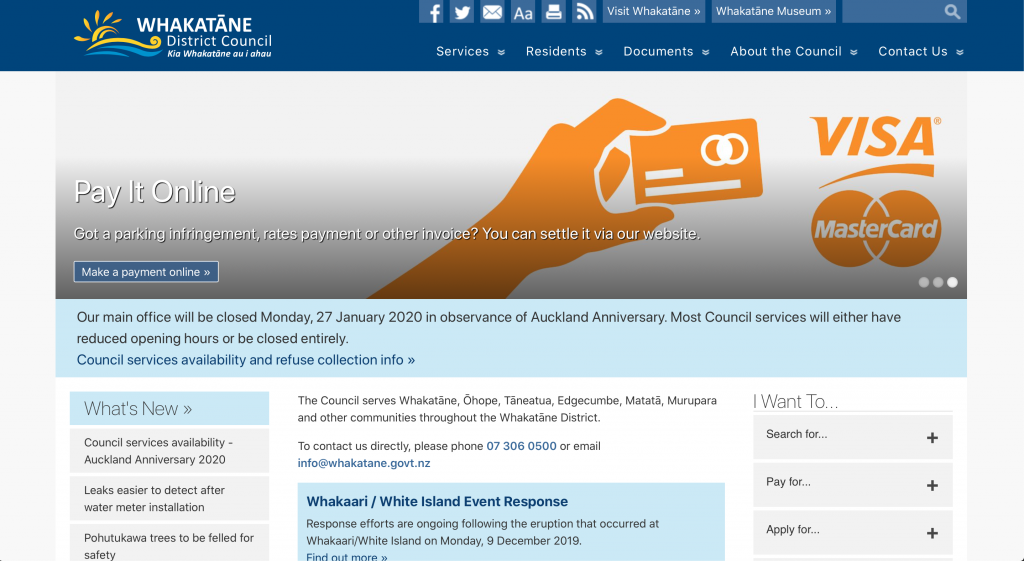

5. Insufficient colour contrast between foreground and background

I usually see this in website design or graphic design more than in web content, but it’s still a problem I see way more often than necessary. Having insufficient contrast between elements in the foreground (text, usually) and the background makes it very difficult to impossible for some people to read. If you were around in the early days of the web, you might remember people’s personal websites had an often, um, creative approach to the colours they’d use — purple text on a lime green background is one example that still haunts me 25 years later.

There’s a good reason most websites have a white background with black text (or vice versa): that’s the widest possible contrast between two colours, and therefore the easiest way for our eyes (and brains) to distinguish between two elements laid on top of one another. If you have light grey text over a dark grey background, or orange text over a yellow background, people are going to have a much harder time seeing it.

There are several online tools that can evaluate colour contrast and let you know whether the difference between foreground and background colours is good enough for most (if not necessarily all) people. The one I usually use is the snook.ca Colour Contrast Check, though there are many others that do the same thing.

6. No ALT text on images

You’ve put a picture of a dog standing on a beach in front of a glorious sunset on your website. Almost everyone will see this cool picture — but not everyone. Blind users with a screenreader will come across this image, and if you haven’t put in what’s known as ALT text, their screenreader will do one of two things: skip right over the image, or worse, read out the image file name. Google’s web crawler will come across this image, but without ALT text to identify what it is, it won’t know what to make of it, and it might not show up in search results.

Here’s a worse example that I’ve seen way too many times in the government web space: You have a neat graphic of a complex workflow or a statistical graph that, for whatever reason, you can’t provide in any format other than as an image. So for anyone who can’t see the image without the help of a screenreader, all the text that’s inside that image might as well not even exist if you haven’t put in any ALT text to provide context for them.

The easiest way around this is to just not use images at all, but that’s either no fun (in the case of dog pictures) or impractical (for graphs and similar content). The next easiest way around the problem is to use ALT text with every image you put on your website, if that image is supposed to convey something other than pure decoration. Use just enough text that a blind user (or Google) can identify the essential purpose of the image (or whatever text the image might contain). You don’t have to go crazy and write a novella-sized description — in most cases, a sentence or two is more than enough.

7. No captions on videos

I don’t know how many times someone in a government department has sent through a video that had to go up today, urgently, but their video didn’t contain captions and couldn’t be published until it did. Videos without captions don’t meet accessibility guidelines for the same reason that photos without ALT text don’t either: for a statistically significant part of your audience, a video without captions won’t do them any good at all.

Usually we talk about deaf users when we talk about people needing captions for videos, but it goes beyond that — they can be very helpful for people who don’t have English as their first language, or for people who have trouble understanding whatever accent people are speaking in throughout the video (imagine someone from the USA trying to understand a video from Scotland without captions, or someone from China trying to understand New Zealanders). People may also be watching your videos in an environment where they can’t hear very well (like on a train or bus) or they may be somewhere that they don’t want sound playing but still want to get the information in the video (trying not to wake up their roommate, or not wanting everyone in the house to know they’re watching a video about getting treatment for an STD).

Relying on YouTube’s automatically-generated captions is pretty much a recipe for disaster. They do an okay-ish job when the speaker has an American accent and isn’t using any slang or technical terms, but if (as just one example) your speaker has a New Zealand accent and is using a lot of Māori language, YouTube is going to absolutely mangle the captions more often than not.

Creating captions isn’t difficult — you literally just have to type out what people are saying into a plain text document and upload that alongside your video. It can be pretty time-consuming, however.

Why you should care about accessibility

Beyond just wanting to make sure that your website’s content can get out to as many people as possible, there’s a very good reason to want every website to be as accessible as it can be: someday, you yourself will need it to be. You will get older, and your eyesight will start to fail. Your hands might start to shake. You might have trouble understanding words and concepts that used to come easily to you. On a long enough timeline, you will need websites to have a basic level of accessibility if you want to be able to use them at all. You might not be blind, deaf, paralysed, or cognitively impaired to a profound degree, but at some point you will be old enough that reading tiny text, tapping tiny buttons, and understanding lengthy jargon-filled sentences will be difficult. If you can’t find it in yourself to make your website accessible for everyone else, do yourself a favour and make it accessible for the future version of you.